2012 marked the 30th anniversary of the

Insight Theatre Company, a touring teenage troupe that expresses the concerns,

emotions and situations of themselves and their peers through improvised

scenarios. The troupe is sponsored by

Planned Parenthood, Ottawa, and I was fortunate to direct and produce the first

company for them.

At the time, I was working for Stage Fright, a local theatre

company that was producing the Canadian Improv Games, a competitive improv

format for teens, inspired by David Shepherd’s Improv Olympics. Planned Parenthood, Ottawa, contacted Willie

Wyllie, the head of Stage Fright, to attend a performance of the Youth

Expression Theatre, a teenage troupe sponsored by Planned Parenthood,

Boston. The audience consisted of health

officials, teenagers and teachers with the Carleton Board of Education. Willie

invited me along.

Planned Parenthood, Ottawa, wanted to develop a similar

program for teenagers. At the time, I

had no idea Willie had already chosen me to produce and direct the Ottawa

company. Therein lies the reality of my

thirty-plus year friendship with Willie.

He allowed me the luxury of believing that I had freedom of choice, when

in fact a decision had already been made on my behalf. But, I digress.

I had never seen anything quite like the Youth Expression

Theatre before. The Boston teenagers,

with an age range of 15 to 18, were edgy, acerbic, confident and had an element

of danger about them. The scenes were

designed to increase awareness, provide information and encourage discussion of

controversial subjects relevant to teenagers.

The scenes all had unresolved endings, so that the cast could engage the

audience in a dialogue after the performance.

I was in awe of the intensity and candor of the actors

during this portion. Their accessibility

made it easy for the teens in the audience to engage in hard-to-discuss

topics. There were two parts to this

discussion, first with the cast in character, then as themselves. They did not seek to offer judgment or

present a particular point of view with these scenes. One particular scenario involving a girl who

brings her date home only to discover that her parents were not there, got the

most questions. She didn’t want to get

involved sexually, but he did, becoming increasingly aggressive until he

finally raped her. The girl who played

the assault victim said she had doubts about joining the troupe, because she’s

Catholic and her family was disturbed by Planned Parenthood’s involvement. After giving it some thought, she realized

that the program’s educational input would prevent abortions. There was a rousing round of applause at this

statement.

What I learned afterwards, was that this type of show was a

Theatre-In-Education (or T.I.E.), production – which is an umbrella term for a

technique that utilizes all the elements of theatre as a teaching tool. I eventually got my Master’s degree in this

discipline at New York University.

My first concern was whether Ottawa teenagers could pull off

a show like this. At the time, I viewed

Canadian teens as simply “nice” and wondered if they were capable of the

honesty, courage and self-awareness needed for this type of production, whereas,

my thinking about Boston teens was that they had the advantage of living in a

city where controversial subjects were discussed openly. Although teenagers in Ottawa experienced the

same pains of adolescence as the Boston group, they displayed it on a more

subtle level.

Willie and I contacted about forty teenagers in Ottawa, to

be interviewed at the Planned Parenthood main office. All of them played in the

Canadian Improv Games, so, from the start, a big plus was that I was going to work

with teenagers who already had a strong foundation in improv. At the interview, we broke the kids up into

four groups. Willie, myself and two

Planned Parenthood officials led discussions on topics such as sex, school,

drugs, and parents. Afterwards, we

compared notes, made suggestions as to who to call back, and eventually we had

our troupe – sixteen members, which eventually shrank down to ten.

|

| Cast with Jack Eyamie of Stage Fright (bearded gentleman) & director (mustache) |

|

At the first workshop, I kept thinking to myself “God, these

kids are so white!” I assumed most came

from middle to upper middle class families.

Turns out, many came from families close to the poverty level and had to

work after school jobs to help out. A few

came from single parent families, or were living on their own with a relative

or friend.

For the first few weeks, the girls would sit on one side of

the room and the boys on the other. As

the discussion sessions became more personal and open, the boys were able to

become more sensitive and aware of the needs of the girls, and vice-versa. The mingling began. After each rehearsal we would go out for

coffee and talk about what transpired in the workshop. I was trying to discover what these teens

felt, what they needed, and what I discovered surprised me, and slowly

destroyed my preconceived notions about Ottawa teenagers.

In intensive rehearsal sessions, theatre skills were

integrated with education in the areas of teen concern. I shifted their improv focus from comedy and

exaggerated characters to realism, emotional sincerity, and approaching the

scenes with an activity- based perspective, rather than a verbal one. Applause was prohibited at rehearsals, to cut

down on the temptation to entertain. I

had seen teams at the Canadian Improv Games present scenes dealing with issues

such as dating and peer pressure before, but the depth potential was barely

scratched.

In the beginning, my emphasis was on familiarizing the group

with each other. However, physical

contact was very rare in scenes. Whether

it was out of nervousness, being self conscious, afraid of what the group might

think, or what the other player in the scene might feel – there was

resistance. With Spolin’s game Contact,

where a player has to touch the other in a different way every time they speak,

it seemed like I was asking the teens to copulate in front of the group. Another obstacle was that nobody wanted to

play a character that might generate a negative reaction from the audience. They wanted to come off as hip and amiable as

possible. Interestingly enough, when it

came to playing parents, the kids’ roleplaying became extremely realistic –

shouting, shoving and touching!

The warm-ups were designed to delve into personal beliefs

and values. Most effective were Tirades

and Endorsements, a quick “soapbox rant” about what you’re passionate about in

life and what makes you angry. Best

Thing/Worse Thing, a brief commentary on the best and worse thing that happened

to you that day. What I Need/What I Don’t Need – was a great warm-up to

generate empathy in the group. Character

Hot Seat, where a player is interviewed as someone they knew well, provided

valuable information on the world the teenager lives in. All of these exercises provided the

springboard to explore various themes, issues and scenarios in scenes. But, it was Spolin’s Activity that Describes

Yourself game that became a watershed moment with the group.

In Activity that Describes Yourself, a player has to

pantomime an activity that provides us with a glimpse into their life. One by one, members did activities such as

typing, playing sports, cooking, and reading.

Then one player, Sandi came up, sat down on the floor, created a knife

and slowly sliced small cuts into both her arms. There was giggling from the group at first,

then the slow realization sank in that she was serious and the room became

intensely quiet. When she finished, the

group immediately began to question her without waiting for me to facilitate a

discussion.

Sandi was surprised by the reaction from the group. She explained that when she “screws up” or

doesn’t do well in school, she cuts herself as punishment. Apparently, her sisters exhibit the same

destructive behavior. There was a moment

when Sandi felt like she was being judged by the group, and started to regret

participating in the game. Then, the

group proceeded to share examples of their own self-destructive behavior: Warren smacks his head against the wall until

he draws blood or passes out, whenever he loses a hockey match. Celia sits in the snow wearing only a t-shirt

and shorts until she can barely move whenever she doesn’t do well on a

test. Ralf gets on a bus destined for an

unknown area with only enough money for one way when he gets turned down for a

date. Ann places her hand over a flame

to see how long she can hold it before burning herself whenever her parents

fight.

As the discussion continued, with one member after another

revealing aspects of their personalities they had never talked openly about

before, I realized that I had severely underestimated this group. They were self-aware, coping daily with the

painful transition from adolescence to adulthood – and they were all in this

together. This was the beginning of the

family-like atmosphere of the group, complete with honesty and trust.

Various community and social service groups participated in

workshops with the troupe: Our House Drug Rehabilitation Centre, Rape Crisis

Centre, Child Development Centre, Gays of Ottawa, Family Planning Clinic, and

Planned Parenthood, Ottawa. For many of

the parents of the kids, it was important to know that while Planned Parenthood

sponsored Insight, the troupe was not a public relations tool for the

organization. I was shocked by the

misconception the public had about Planned Parenthood and frequently had to

remind people that the organization was not against pregnancies, but rather

unwanted pregnancies. Also, family

planning was just part of the services Planned Parenthood provided. Again, this was thirty years ago, although,

there are days when it seems like not much has changed with the public’s

conception, if you forgive the pun.

After each presentation, we would brainstorm scenes, and

then start improvising. The method used

to develop scenes I learned from David Shepherd and Paul Sills, who constructed

scenes for Compass, the first professional improv company in the United States,

in this manner: As the players started

improvising, I would write down important “beats” in the scene, which is any

significant change in action or an important piece of dialogue. Once a beat outline was finalized, the goal

was in cutting the length down to the point where it was as sharp as

possible. This proved most effective

when certain cast members couldn’t attend a performance. All their replacement had to do was look at

the beat outline and they were set.

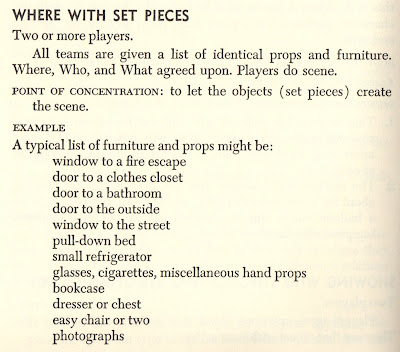

|

| Insight beat outline. |

As the show came together, the issues we were dramatizing

included drug and alcohol abuse, difficulties in communicating with parents and

peers, homosexuality, acquaintance rape, depression, stereotypes and teen

pregnancy. As heavy as this may sound,

there was a great deal of humor in the shows, which always came from the

reality of the situation and characters.

Aside from the workshops, it was up to every cast member to

do outside research. Some developed

relationships with the organizations who participated in our workshops. Others interviewed runaways, drug addicts and

teen parents. Most of the situations we

dramatized were not necessarily ones which the actors had experienced

personally in real life, but there was one notable exception.

Marni, a 18 year-old cast member, had been sexually

assaulted at a costume party by the father of her best friend. The Planned Parenthood associate on the show

and I helped Marni with getting in touch with counselors at the Rape Crisis

Centre and filed a “fourth person report” with the RCMP. Marni did not want to file charges, but if

the father assaulted another underage girl, Marni’s report could be used as

evidence against him.

Few weeks later, Marni stayed behind after a rehearsal and

we started talking about the assault.

She was still very much in the mindset that somehow she was responsible

for the attack, based on the outfit she was wearing at the party, and how

devastated her friend would be when the news got out about her father. I asked Marni if she would be willing to

explore the before, during and after events of the incident through a series of

monologues. Not for the show, but to

help Marni cope with the experience.

Over the course of the next few weeks we worked on the

monologues together privately, and the experience helped Marni cope with the

assault, and more importantly, accept that it was not her fault.

The process of working on the monologues empowered Marni to the point

where she insisted that it be included in the show. It became one of the most powerful moments in

the show, and there were easily scores of young women who came up to Marni

after the show over the course of the tour admitting that they had a similar

experience. At the end of every performance,

we handed out a sheet with contact information for all the organizations that

participated in the production, and Marni made sure each and every girl knew

where to go to get help. Months later,

the man who attacked Marni assaulted another young girl, who did file

charges. Marni’s fourth person report

was used as additional evidence, and he was convicted.

It was not unusual that audience members came up to share

experiences with the cast that they had previously kept private, was not

unusual. Every cast member became an

ambassador for the organizations involved in the show. As the tour progressed, the content of the

show became richer, more complex and instantly identifiable regardless of the

audience we were performing for. Audience

input during the discussion section would change the direction and content of

certain scenes for future performances.

When we had time, occasionally we would replay scenes on the spot, incorporating

the audiences’ suggestions, then go back to the discussion, focusing on the new

approach.

A scene I wish I could have included in the show came out of

an improv after Jim, the head of Gays of Ottawa, conducted a workshop for

us. He had recently left his wife for a

man, and was dreading telling his two children that he was divorcing their

mother and admitting he was gay. I

suggested that he could practice telling his kids, by roleplaying the situation

with two of my players. Intrigued, he

agreed. In the scene, he carefully laid

out why he was leaving their mother, that it had nothing to do with them and he

was gay. Grant, who played his son asked

“But, you still love us, right?” Jim

replied “Of course.” Patti, who played his daughter asked “Do you love this man

and does he make you happy? Jim answered

“Yes.” The scene ended with the kids

telling Jim that they loved him too and were happy for him. It was one of the most moving scenes I have

ever seen in a workshop.

Couple of days later, Jim called me in tears. He had the talk with his kids and amazingly,

it went exactly the way it was played out in the workshop. I asked if he would be willing to give me permission

to use the scene in the show. After some

thought he decided it was too personal and I respected his decision. But, damn – I wanted to use that scene! In retrospect, I should had prodded him

further – reasoning that it could inspire other people to come out.

The troupe toured for 6 months, performing for community

centers, high schools, social service agencies and guest spots on local

television shows. The troupe quickly

became a close-knit group, socializing and at times, dating. Rehearsing scenes away from the workshop was

encouraged. Sometimes, when I felt a

scene was starting to get stale I would recast it right before a performance,

to give it a fresh surge of spontaneity.

I became extremely close to the cast.

Their parents viewed me as a father figure. To the cast, I was a slightly older version of

them.

Willie and I were roommates, and

frequently we had a cast member as a houseguest.

Most cases, it was just to hang with us for

the weekend and help out with administrative work needed for Insight or the

Canadian Improv Games.

But, we had one

long term guest.

Patti’s father suddenly

died of a heart attack while jogging with her mother.

Patti was emotionally shattered and was

ready to leave the troupe and high school, and “hit the road” because the grief

with her large family was unbearable.

We

allowed her to live with us on the condition that she remained in high school, the

troupe, and more importantly – take charge of the housecleaning.

This arrangement worked quite well.

Our apartment never looked better.

|

| 4 1/2 Henry Street Ottawa, home to wayward improvisers. |

One day when I had to go down to New York to see the opening

of a friend's play, Warren offered up his mother's car. One catch.

Warren, Ann, Patti and Ralf were part of the package. I had a catch too, which wasn't revealed

until we arrived in New York. Ralf and

Warren stayed at my parent's house. Anne

and Patti stayed at a friend's place.

All seemed surprised by this arrangement. Nice try, kids. For the record, no cast member became a

parent on my watch.

My role slowly changed from director, to confidante of the

group. If any member of the group had

problems with school, parents, boyfriends or girlfriends, inevitably, they came

to me. I appreciated their openness and

honesty, but had to be careful with how I would use this knowledge –

particularly in rehearsal. In cases

where I would, it was always in private and to provide them with a frame of

reference if the content of a scene wasn’t clicking. I call this technique “Spolin meets

Strasberg.” As for my original impression that these were

lily-white teenagers with privileged lives, that was finally put to rest when

we did a workshop on runaways. Sandi

admitted she ran away from home at 15 to Newfoundland, where she worked as a

prostitute for close to two years and finally returned home after she was

gang-raped and left for dead.

The Insight Theatre Company garnered a great deal of press

and we were suddenly thrust into the celebrity spotlight when Platform, a

current events television show, wanted to do a one hour adaptation of the show. During preproduction, several unexpected

problems arose. First, ACTRA (Association

of Canadian TV and Radio Artists), felt the cast weren’t amateurs, based on the

professional level of their performances.

I suppose it was a compliment, but we didn’t have the $10,000 on hand to

make every member part of the union.

Howard Jerome, one of the founders of the Canadian Improv Games made a

passionate plea on our behalf, and ACTRA changed their decision and granted us

waivers to appear on the program.

Next, the producers of the show were uncomfortable with a

scene between two brothers where one admits to the other that he was gay. Since this was an early morning show, the

producers felt the scene might be offensive to some viewers. When I suggested, as a joke, that I could

change it to two sisters instead, the producers thought that was acceptable,

and that’s the way the scene was presented in the broadcast. Finally, because of the three camera set-up,

the cast couldn’t be as physical as they were in the stage show. So, the scenes either had the actors standing

and talking, or sitting and talking. The

end result came off a little more heavy handed in tone than the stage show, but

was still effective. The broadcast got

high ratings, was repeated a few times, and led to the creation of a four

episode series called “Crisis Theatre” which was essentially Insight for

adults.

Three decades later, I’m still in touch with many of the

troupe members. A few have become

life-long friends. Others, I’ve recently

re-connected with through the magic of Facebook. Most are parents with teenagers of their

own. When their kids complain they don’t

understand them or have forgotten what it’s like to be a teenager, they throw

on the Platform television show, stand back and silently observe their minds

being blown.

Michael Golding is a writer,

director and improv teacher. He can be contacted

for workshops, festivals and private consultations at migaluch@yahoo.com. Michael participated in the evolution of the Improv Olympics

& Canadian Improv Games. Artistic director of the Comic Strip Improv

Group in N.Y. & created the Insight Theatre Company for Planned Parenthood,

Ottawa. He is a faculty member at El Camino

College in Los Angeles, working with at-risk teens and traditional students. Michael holds a BFA degree in Drama from New York University’s Tisch

School of the Arts & an MA degree in Educational Theatre from NYU’s

Steinhardt School of Culture, Education & Human Development.